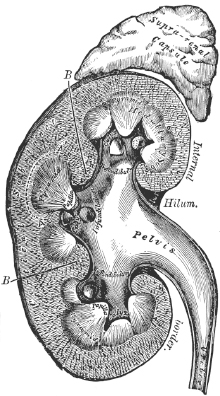

KIDNEY STONES

Stone Disease

Stone formation within the urinary tract is a common problem and the incidence is increasing. About 4-8% of Ausralians suffer from them at some time. The lifetime risk for developing kidney stones is 1 in 10 for Australian men and 1 in 35 for Australian women.

For Dental info refer to DA.

ADDITIONAL INFORMATION

A stone forms when a substance (often calcium oxalate) becomes saturated in the urine and therefore forms solid crystals. These crystals can clump together to form a stone. If very tiny they can pass out without causing any trouble but if they grow (usually to a size greater than 2-3mm then they will often cause pain if they pass down the ureter (pipe from kidney to the bladder) and may get stuck.

The majority of stones contain calcium and the most common stone type is calcium oxalate. Uric acid stones can be associated with obesity and are also increasing. They can be more difficult to diagnose and monitor as they cannot be seen on plain X-rays. The most common stone types are listed below:

- Calcium oxalate 60%

- Calcium phosphate 20%

- Uric acid 5-10%

- Magnesium Ammonium Phosphate (Infection) 5-15%

- Cystine 1%

- Others 1%

Your urologist will look at your risk factors for getting stones with the aim of identifying any metabolic reason why they form. The chance of developing a stone increases if you have a family history of stones. The risk also increases as you get older. Modern diets and lifestyles are often to blame and dehydration is a major aggravating factor.

Stones can sit in the kidneys and be asymptomatic or can cause grumbling pain in the loin region. When stones get stuck in the ureter they can cause very severe pain. This can start in the loin and move round the groin and radiate into the testicle or perineum. When stones are close to reaching the bladder they can also cause a need to pass urine more frequently. Often they can cause some bleeding in the urine. If you have a urinary tract infection, you may develop a high temperature. Having a kidney stone AND a high temperature may necessitate emergency treatment. Contact your doctor urgently or go directly to the emergency department of your nearest hospital.

Your urologist will take a careful history from you looking at the current episode and any previous problems including family history. The gold standard for diagnosis of kidney stones is a CT scan although monitoring of stones is usually done with x-ray or ultrasound. You will also need urine and blood tests.

This will depend on a number of factors such as the size of the stone, location, symptoms, presence of fever, findings of the urine and blood tests and also patient choice. In principal stones can be treated by:

- Observation – Small stones will often pass without treatment and if symptoms are manageable it is often safe to leave them for up to 2 weeks. Your urologist may start you on medication to help stones pass.

- Shock wave lithotripsy – The procedure works like ultrasound and uses shock waves to break your kidney stones into small sand-like particles that can then pass out of your body through your urine. It is performed as a day procedure and avoids the need for a general anaesthetic. During the procedure, you lie on the machine and x-rays are used to find and target your stone. Shocks are then delivered to the stone. The treatment lasts about 40 minutes and delivers around 3,000 shock waves, which pass through your body to break the stone into fragments. It is not suitable for all stones and your urologist will advise you on this. Success rates vary depending on stone size, composition and location.

- Ureteroscopy – This is a procedure that involves a fine telescope being passed through the bladder (via your urethra) and up the ureter to the kidney. It is performed under general anaesthetic. Once the stone is found a laser is used to fragment and vaporise the stone into tiny pieces. Usually the holmium laser is used which is able to break all types of stone. This procedure is generally suitable for stones up to 1.5cm in size and usually takes 60 minutes to complete. Commonly a plastic tube (known as a JJ stent) is inserted afterwards – this runs from the kidney to the bladder and allows the urine to drain and protects the ureter.

- Percutaneous surgery (PCNL) – This is used for larger stone burdens in the kidney which are generally not suitable for lithotripsy or ureteroscopy. A telescope is placed through the back using X-ray guidance with the aim of removing large volumes of stone. It is performed under general anaesthesia and usually requires 2-4 days in hospital.

Your urologist will discuss with you in detail the above treatments to ensure that the correct treatment is tailored to your needs and your stone burden/ location.

Stone formers have a high chance of recurrence (50% at 5 years). Once your stone has been treated, your urologist will look at any specific factors in your blood and urine that may need correction to help prevent future stone formation. If a stone has been removed then usually we will be able to tell you the type of stones that you form, so that preventative advice can be tailored to your individual needs. This may require modifying dietary factors and increasing your fluid intake. Most stone formers should aim to produce 2 – 2.5 litres of urine per day.