BLADDER CANCER

- Each year about 3000 people in Australia are diagnosed with bladder cancer.

- Bladder cancer can usually be effectively treated, especially if found early, before it spreads outside the bladder

- Smoking is one of the most common causes of bladder cancer.

- Bladder cancer becomes more common as people get older.

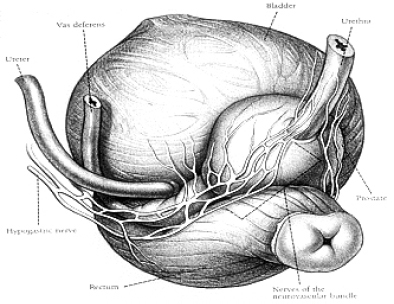

The bladder is a hollow, muscular, balloon-like organ in the lower part of the abdomen that collects and stores urine. It is connected to the kidneys by tubes called ureters, and it opens to the outside of the body through a tube called the urethra. In women the urethra is a short tube that lies in front of the vagina. In men the urethra is longer and passes through the prostate gland to the tip of the penis.

The inside of the bladder is covered with a urine-proof lining called the urothelium, which stops urine from being absorbed back into the body. The cells that make up this lining are called transitional cells or urothelial cells.

ADDITIONAL INFORMATION

Some of the possible causes of bladder cancer, or risk factors for bladder cancer developing include:

Smoking

This is the biggest risk factor for bladder cancer. The longer a person smokes and the more cigarettes they smoke, the greater the risk. Chemicals that cause bladder cancer are present in cigarette smoke. It’s thought that these chemicals get into the bloodstream and end up in the urine after being filtered by the kidneys. They then damage the cells that line the inside of the bladder. It takes many years for these chemicals to cause bladder cancer.

Exposure to chemicals

at work These include chemicals previously used in dye factories and industries that worked with rubber, textiles, printing, gasworks, plastics, paints and chemicals. The link between these chemicals and bladder cancer was discovered in the 1950s and 60s, so many of them were banned. However, it can take more than 25 years after exposure to these chemicals for bladder cancer to develop.

Age

It’s unusual for anyone under the age of 40 to get bladder cancer. It becomes more common as one gets older.

Gender

Bladder cancer is more common in men than in women.

Infection

Repeated urinary tract infections and untreated bladder stones have been linked with a less common type of bladder cancer called squamous cell cancer.

Bladder cancer may appear in different forms, and these include:

- Transitional cell bladder cancer (TCC)

- Carcinoma in situ(CIS)

- Papillary cancer

- Rarer types of bladder cancer

TCC, also known as urothelial carcinoma, is the most common type of bladder cancer. The cancer starts in cells, called transitional cells, in the bladder lining (urothelium).

Some bladder cancers begin as an invasive tumour growing into the muscle wall of the bladder. Others begin at a non-invasive stage that involves only the inner lining of the bladder – this is early stage (superficial) bladder cancer. Some non-invasive cancers develop into invasive bladder cancer.

This is a type of non-invasive bladder cancer that appears as a flat, red area in the bladder. CIS can grow quickly if not treated effectively, and there’s a high risk that CIS will develop into an invasive bladder cancer.

Papillary bladder cancer is a form of early bladder cancer. It appears as mushroom-like growths. Some people may have both papillary cancer and CIS.

These include squamous cell cancer and adenocarcinoma. Squamous cell cancers start from another type of cell in the bladder lining. Adenocarcinoma starts from glandular cells. Both of these types of bladder cancer are usually invasive.A

The most common symptoms of bladder cancer are blood in the urine (haematuria), bladder changes and pain in the lower part of the abdomen or back.

This is the most common symptom. It generally happens suddenly and may come and go, but it’s usually not painful. Blood in the urine may make the urine look red or brown, or you may be able to see streaks or clots of blood in the urine. Sometimes blood in the urine can’t be seen and is picked up microscopically by a urine test.

If you have other bladder symptoms, your urologist will usually check your urine for microscopic amounts of blood. It’s important that people over 50 years who have microscopic haematuria are investigated for cancer. If you see blood in your urine at any age, you should always go to your GP or urologist and get it investigated.

Bladder irritation symptoms include having a burning feeling when urinating or feeling the need to pass urine more often or urgently. These symptoms are more often caused by infection rather than cancer. However, sometimes more tests may be needed.

This is less common, but it may occur in some people.

These symptoms may not be bladder cancer. Common conditions such as an infection or stones in the bladder or kidneys are often the cause.

- Seeing your GP or urologist

- Tests for bladder cancer

Your Urologist will ask you about your symptoms and general health, and arrange the following tests.

Blood and urine tests

Cystoscopy – a specialist nurse or doctor uses a cystoscope (a thin tube with a camera and light on the end) to look at the inside of your bladder.

Ultrasound scan – this uses sound waves to look at internal organs

CT scan (computerised tomography) – a series of X-rays that builds up a three-dimensional picture of the inside of the body.

Intravenous urogram (IVU) – a dye is injected into the bloodstream and passes through the urinary system to show if there are any problems.

MRI scan (magnetic resonance imaging) – uses magnetic fields to build up a series of cross-sectional pictures of the body.

Bone scan – a scan of the whole body to show any abnormal areas of bone.

Grading and staging of bladder tumours

- Grade 1 tumours are less aggressive

- Grade 2 tumours are moderately aggressive

- Grade 3 tumours are most aggressive and most likely to spread.

The extent of the tumour is called its stage. Treatment option depends on the stage and the grade of the tumour.

- Superficial

- Carcinoma in situ – bladder cancer cells are completely contained on the inner surface of the bladder lining.

- Stage Ta – affects the epithelium. In most superficial cancer stage, the tumour is confined to the inner layer of transitional cells. Provided the grade is 1-2, this is very unlikely to progress.

- Stage T1 – the tumour has started to invade the inner layer of muscle of the bladder (lamina propria), but has not reached the detrusor muscle.

- Invasive

- Stage T2 – the tumour has spread into the muscle layers of the bladder wall.

- Stage T3 – the tumour has spread through the deeper muscle layers into the surrounding fat.

- Stage T4 – the tumour has spread beyond the bladder into areas around the bladder, e.g. prostate, vagina, bowel and or other parts of the body.

After treatment, it is normal to have regular follow-up cystoscopies, every 3 months to check that the tumour has not returned.

Sometimes these checks can be performed using flexible cystoscopies every 6 or 12 months to ensure that if the tumour does return, it is removed as early as possible.

We may recommend surgery, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or a combination of these for treating your bladder cancer, keeping in mind that preserving or re-creating the bladder is the key consideration.

Most bladder cancers are diagnosed at an early stage. Your chance of surviving this disease is very good when it’s caught early and you receive prompt treatment. Surgery is a good option for many patients with early-stage disease.

If your cancer is more advanced and has spread beyond the bladder, we may refer you to a medical oncologist for chemotherapy or new drugs or combinations of drugs available through clinical trials. Some trials test new drugs while others aim to make improvements to existing treatments.

Treatment option for invasive bladder cancer

- Cystectomy with: ileal conduit formation, neo bladder replacement and continent urinary diversion

- Radiotherapy

- Chemotherapy:

- Intravesical – directly into the bladder (chemotherapy and immunotherapy)

- Intravenous- into the bloodstream, via a vein

- BCG treatment

Surgery is usually the first treatment for bladder cancer that has not spread to other parts of the body. We understand that you want to return to your normal day-to-day activities as soon as possible, and my skilled surgical techniques can limit your side effects and speed your recovery.

A number of surgical options are available for bladder cancer patients. These include:

- a minimally invasive procedure called cystoscopy for stage 0 and I transitional cell carcinoma (TCC)

- techniques to avoid bladder removal and preserve your sexual health

- bladder reconstruction (called a neobladder) for patients who do have to have their bladder removed through a procedure known as radical cystectomy

- BCG therapy to minimise the risk of recurrence

For some patients, Dr Ruban may recommend chemotherapy first to make the surgery more effective.

Dr Ruban will make a recommendation based in part on how advanced the disease is (itsstage) and whether you’ve already had prior treatment for bladder cancer.

If you’re at high risk for your bladder cancer returning after surgery, we may recommend that you receive bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) therapy. Given once a week for six weeks, this therapy is designed to trigger an inflammatory response in the bladder that prevents the tumor from growing.

To give you BCG therapy, our doctors deliver inactivated tuberculosis bacteria directly into the bladder through a catheter (a small tube) placed in the urethra (the duct through which urine is transported out of the body).

In some cases, early-stage bladder cancers do not respond to BCG therapy. If your bladder cancer returns, we may recommend you take other drugs, including certain chemotherapy drugs, instilled into the bladder via your urethra to lower this risk. We’ll likely want to examine you every few months after your therapy ends to make sure that your bladder remains healthy and tumour free

Chemotherapy is a drug or a combination of drugs that kills cancer cells wherever they are in the body. Medical oncologists specialise in chemotherapy for bladder cancer and will carefully tailor your treatment to make sure that it’s as effective as possible while helping maintain your quality of life. For example, if you’re an older patient, your medical oncologist can recommend specific chemotherapy treatments that will minimise your side effects